Research topics

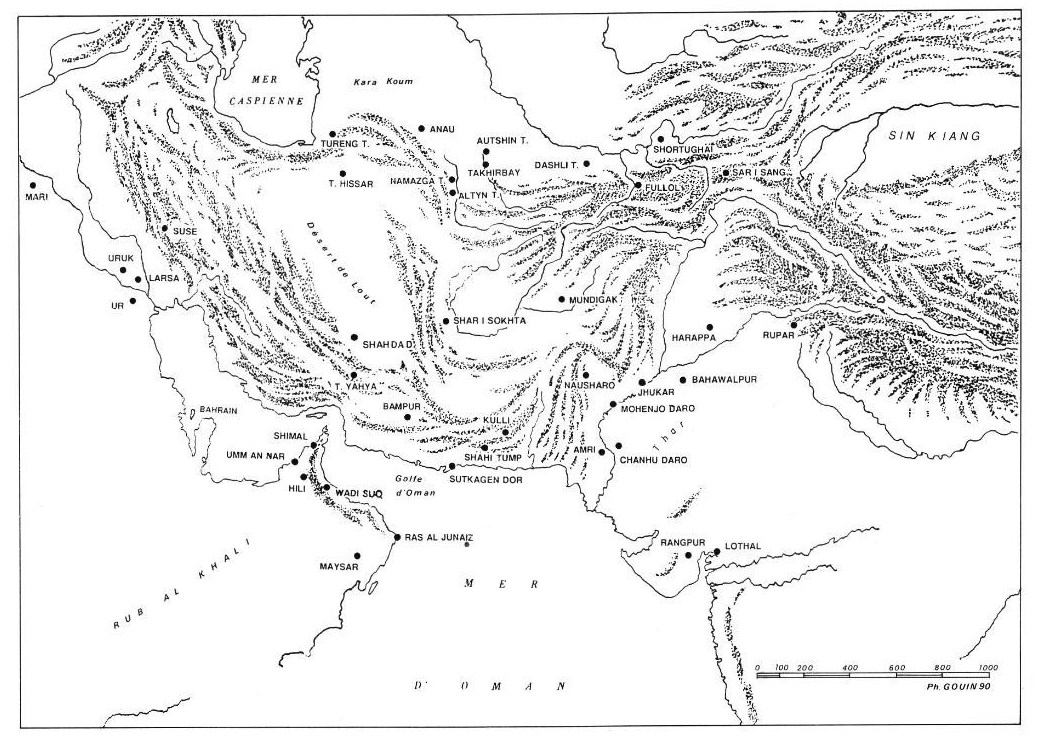

New identification methods of food products and techniques from Middle Asia to the Eastern Mediterranean

original version

You will find below some of the research topics to which I have devoted all my attention for nearly fifteen years, from 1990 to 2004 (extracted from Gouin Ph., Scientific Activity Report - CNRS, 1997).

Theory

- Archaeology of perishable food products

The archaeological studies were, for a long time, limited to the study of the reigns, religions and prestigious monuments. The temples and palaces of vanished empires are thus better known than the daily activities of their builders. The food practices constitute an innovative and as yet little-explored field of research, because of the highly perishable nature of food products and of the scarcity of historical materials and archaeological evidence on their production process, from their preparation to their consumption. Studies on the ancient food technologies were thus unfortunately rare and related to the periods and the cultures which have left documents (Ancient Egypt, classical Antiquity, Western medieval period...).

Some people will think that it is of little importance to know how our ancestors ate their food, the nomenclature of basic foodstuffs having hardly changed since the Neolithic, with the exception of some notable imports of tomatoes, potatoes, etc.... However, ancient food products differed from those consumed today, not only by their gustative qualities, but also by their agricultural qualities. Indeed, our vegetables are bigger, our fruits sweeter and our cereal more resilient than formerly thanks to selections over thousands of years. Furthermore, the number of natural food has been significantly restricted over time. Today in our regions, we only eat a small number of the plants and animals consumed by our ancestors. Finally, many ancient recipes and food preparations are now completely forgotten, the taste of consumers having changed considerably.

The food habits are generally rather faithful markers of the economic, technological and cultural practices of the vanished civilizations. They were very dependent indeed on the climate, the local resources and the skill of the people. According of the peculiarities of its geographical, technical, social and cultural environment, every ethnic group consumes and gets ready its food according to typical culinary combinations. These end in the creation of regional cuisines which reflect rather faithfully the deep personality of those who consume them : it will be for instance the grilled bark worms consumed by the Papuans of New Guinea (hunters-foresters) or the fillet of sole with cream sauce consumed by the Normans of Normandy (fishermen-breeders). The study of the food of an ancient community is thus one of the good means to approach the analysis of vanished civilizations.

- Fundamental principles

The analysis and the recording of the oriental, antique or traditional food activities enabled me to develop working strategies and procedures, easily adaptable to the study of many other craft sectors. They are based on three fundamental assumptions :

These fundamental principles so allow us to use most of the traditional crafts as models in order to reconstitute the ancient activities related to the production of perishable products (wood, leathers, food, etc.). This results in the following equations :

back to top

Practice

- Empirical identifications

Although foodstuffs quickly disappear without leaving any obvious traces, it is sometimes possible to find them by identifying the utensils that have been used during their preparation, their cooking and/or their transportation. As the other tools used by the specialized craftsmen, the food utensils are the witnesses of the techniques they helped to implement. Therefore, in the same way that the adze infers the work of timber, the churns imply the preparation of butter and the cheese-drainers suggest that of cheese. By this way and by using the principles set out above, certain food preparations and consequently the production, the consumption and the trade of certain foods can be reconstituted. To find the function of the characteristic archaeological tools of a domestic or craft technique thus becomes of an exceptional interest by the number and the quality of the inferred virtual information.

All the difficulty of the use of such a system is in distinguishing significant marker artifacts among thousands of other objects discovered in the archaeological excavations. To this end, we use a proven comparative method the simplicity of which is only apparent. If we accept that ethnic groups, whose socio-cultural, technical and geographical environments are comparable, use similar utensils, it becomes possible to identify archaeological technical objects by comparing them to their current traditional counterparts. The existence of certain perishable foods so revealed by the identification of utensils, it is possible to reconstitute their technical development and their implementation as well as some of the underlying socioeconomic structures, strongly dependent on peculiarities of the ecosystem. The analysis of the technologies and the food practices so contains many facets and the archaeologist will have to appeal not only to all the branches of the humanities, but also to those of the sciences of life and matter.

This analysis system may be represented by the following diagram :

back to top

- Iconographic and textual data

The household objects, discovered in the archaeological excavations, are obviously not the only sources of information on the ancient food practices. The Mesopotamian and Egyptian texts will undoubtedly bring valuable information about the various food production and trade channels. On the other hand, the Harappan texts are still indecipherable. But perhaps one day, it will be possible to establish a parallel between the inscriptions found on the vases and their function or their content, the first steps toward the understanding of this language. We have to add to this research, those I have undertaken for several years on the dairy iconography. The Harappans did not practically leave images of their everyday life, with the exception of a few statuettes, seals decorated with finely engraved animals and ceramics with naturalistic decoration. On the contrary, the Mesopotamians and the Egyptians were used to representing their everyday-life on sustainable materials. An important source of documentation on the breeding and the dairy activities is thus available in the publications and in the museums of East and West. That needs only to be studied.

back to top

- Archaeometric data

Until the late 1980s, the information obtained by ethnoarchaeological deductions was mainly based on assumptions. More refined techniques of archaeometric analysis have since allowed us to determine the nature of numerous types of ancient organic residues trapped in the walls of pottery vessels. Thus it becomes possible to explore some research areas where visible remains are lacking. However, as almost always, this new archaeometric tool was not developed especially for archaeology. The research was done mostly by scientists who agreed to distract a little from their time and their resources to archaeology. If it allowed some interesting discoveries, these collaborations remained nevertheless limited to punctual analyses and, it must be said, often anecdotal. The results ended only in the publication of technical notes without real interpretation whose scientific benefits were difficult to evaluate.

At that time, spectrometric analyses of archaeological food traces were still very little developed in France. They were mostly practiced in the English-speaking world. The North American, British, Canadian and New Zealander researchers so obtained amazing results. Some, as M. Deal for example, reconstituted the National Indian food through some chromatograms carried out on samples of ceramic vessels used during the preparation of their food. Others, like H.E. Hill and J. Evans, managed to show the presence of residues of banana, sweet potato, taro and rice in vases discovered in the Pacific Islands. Finally, R. Rottländer managed to compile numerous data in his catalogue of lipid chromatograms allowing the identification of certain kinds of archaeological food residues. In view of these results, one might think that the use of gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry to determine the nature of organic residues found in archaeological utensils was very promising. But it was still necessary that the two disciplines define together a problematic before starting such costly analyses.

Such tandems produced good results if we judge by the joint study of a vase of the third millennium from the Harappan site of Nausharo in Pakistan. The studied samples belonged to ceramic utensils the walls of which was drilled with numerous small holes. Their shape, close to that of the cheese-drainers still used nowadays in the West, allowed to imagine their function. These vases existed in any sizes, from the tiny cheese-drainers-toys to the largest, adapted to the processing of the milk of a herd. The perforations in their wall allowed the draining fresh cheese without the curd can escape. In addition, a large hole was drilled into their bottom in order to push and extract the contents of the vessel after draining. Finally, a fortunate coincidence of the excavation delivered us one of these objects still in place on the plate intended to collect the whey of draining. As a result, the use of this vessel as a cheese-drainer thus became highly probable.

Furthermore, the hypothesis of the existence of dairy utensils in the ceramic material of the Indus Civilization was strengthened by the cultural context of the region. We indeed know that in the Subcontinent, the cow and milk are still considered to be of sacred origin. The Harappan iconography (finely engraved seals, votive statuettes or toys) and archaeozoological studies show us moreover that the milk-producing bovids (cattle, sheep, goats) were already omnipresent in the third millennium in the economy of the Great Indus Valley.

Samples of walls and bases of cheese-drainers were thus submitted to chemical analyses by gas chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry. These analyses were performed by the Laboratory of the CESAMO (URA 35 of CNRS-Bordeaux I University) and supervised by G. Bourgeois. The work of the chemists was made easier by some favourable circumstances linked to the nature of the samples :

Without any doubt, these favourable conditions contributed a lot to the success of the analysis which showed that the cheese-drainers samples contained traces of an organic compound similar to goat cheese.

back to top

- Interpretative data

The confirmation of the hypothesis of the use of a simple drilled vase of the Indus as cheese-drainer exceeds by very far its anecdotal aspect. It is exemplary in fact because it makes us reach a long chain of deductive reasonings. Exploited in an exhaustive way, this leads us to an important sum of virtual information on the technical conditions of its use and on the socioeconomic structure of the Great Indus Valley in the third millennium B.C.

Here are as an example some of the most interesting points which we can get from the deductive analysis of the Harappan cheese-drainer.

back to top

- Limits of the virtual information

We well realize the importance and the variety of the data obtained by the analysis of a simple cheese-drainer. Almost all the aspects of the socioeconomic structures of the Indus civilization are mentioned. Most of these data are of course hypothetical but it is surprising to note that they share many similarities with current models. But let us not be too optimistic. We will miss for a long time important data to brush a complete picture of the food supply of the people of the ancient Oriental Civilizations. Indeed, if the system described above allows to reconstruct, with a certain degree of reliability, some of the processes of preparation of the dairy products of an ancient culture, it is for example impossible to determine the exact character of the obtained products. The time and the degree of fermentation or drying of elements and finished product, the addition of spices, which determine the appearance and taste, are still undetectable. To imagine them, we can rely only on comparisons with current equivalent products, what means that the essential ethnoarchaeological models must be recorded before they disappeared in front of the industrial and international globalist tidal wave or the armed conflicts.

back to top

- Empirical identifications